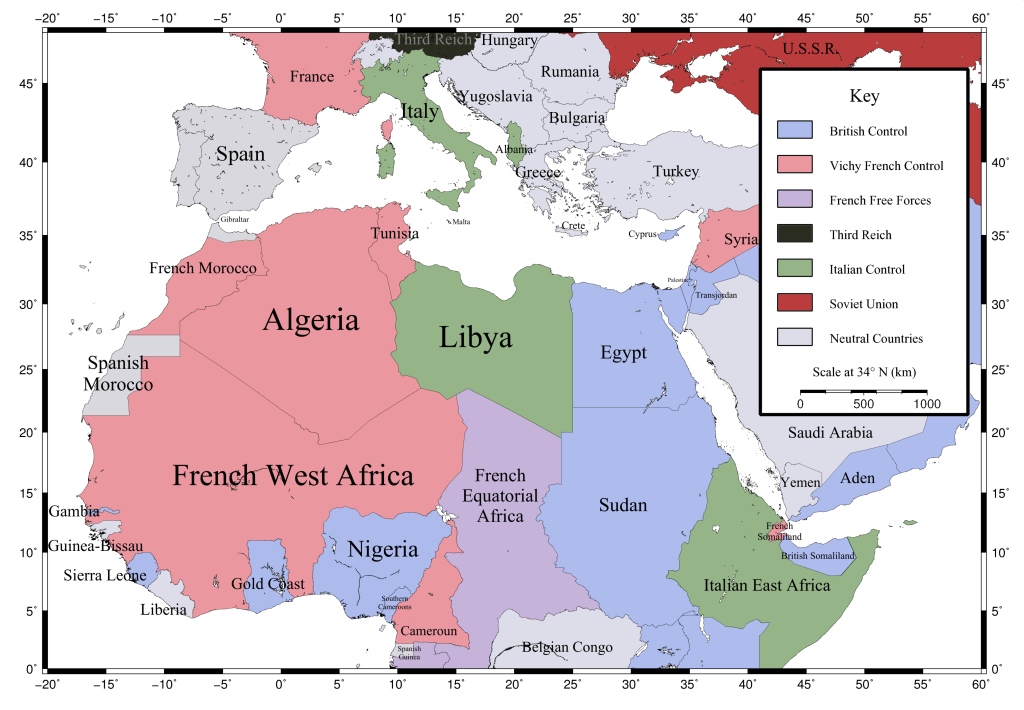

Some of the very first action in WWII took place in North Africa and the Middle East. By the 1930s, most European powers – predominantly the Allies – had economic interests in the region. The new fascist powers of the era wanted a piece of the area too, and in 1935 the Italians began expanding their hold on East Africa with the Invasion of Ethiopia. Tensions rose as the decade wore on and British and French troops reinforced their holdings, particularly in the Middle East. Conflict in the region was inevitable. On June 10th, 1940, the Italians declared war on the Allies and the North African Campaign of WWII began.

ASAP: European colonial tensions came to a head at the outset of WWII, and superior Allied numbers eventually won out over the Afrika Korps and less-competent Italian troops.

Read on for details!

The Western Desert Campaign

As France fell to the Axis blitzkrieg (lightning war) in May, British troops in Egypt knew to expect trouble. Italian troops began reinforcing their garrisons in Libya. In early June, the Brits began raiding Axis positions and harassing their supply lines, and their regional commander – General Archibald Wavell – pleaded with his superiors in England for reinforcements. At the time, British war planners were expecting a full-on assault from across the Channel by the newly-dominant German forces; little to no help arrived for Wavell. The situation became increasingly desperate as Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini ordered an offensive against British Egypt – but luckily for Wavell, the Italian army was largely incompetent and Mussolini’s order was ignored. However, in early September the Italians reluctantly advanced towards Mersa Matruh, the new British position in Egypt.

The Italians made decent progress but by mid September their supply lines were falling apart. The British launched Operation Compass, an effort to harass and destroy the enemy advance. 36,000 men of the British Commonwealth Force attacked and soon nearly 100,000 Italians were fleeing West, their attack on Egypt all but forgotten. In the ensuing 10 weeks, the Brits chased the massive Italian force all the way to El Agheila, a port in the far west of Italian Libya. Over 130,000 Italians were captured by the tiny British force.

Operation Compass also saw one of the first uses of special forces during WWII. The brand-new Special Air Service – the brainchild of eccentric painter and explorer Lieutenant Colonel David Sterling – was a 60 man detachment who parachuted into the desert and essentially snuck around getting into “ungentlemanly engagements”: ambushing and sabotaging the Germans. The tiny unit was hated by most conventional British officers, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (a romantic who loved daring stories) supported the SAS and ordered its expansion. Throughout the rest of the campaign, the SAS tore around the desert in modified Jeeps and shot up Axis airplanes far behind enemy lines. The strange, bearded men of the SAS had an outsized impact on the Afrika Korps, who became terrified of the unit and were forced to devote more men to guarding their airbases. Stirling’s strange new unit went on to fight in Europe, and was the inspiration for special units the world over in the ensuing decades.

The Desert Fox Arrives

By February of 1941, it was becoming increasingly clear to German Fuhrer Adolf Hitler that the Italian Army was far from the elite force of fascist supermen Mussolini made it out to be. Italian units were pulled from Europe and sent to reinforce the heavily-depleted force in El Agheila, while Hitler grudgingly sent a force of his own – called the Afrika Korps – to help. The Korps was only a few divisions strong, but it was complemented by huge numbers of Italians. Concurrently, much of the Allied presence in North Africa was withdrawn to reinforce Greece against the impending Axis attack. In the winter and spring of 1941, commander of the Afrika Korps General Erwin Rommel (AKA the Desert Fox) faced off against new, inexperienced British troops of the XIII Corps.

Despite orders to hold a defensive position, Rommel began raiding Allied positions. Hitler hated being disobeyed, but a man named “the Desert Fox” was surely not going to wait around for orders. Luckily for Rommel’s reputation, the raids were a success; soon, the Australian 9th Infantry Division was besieged at Tobruk in Libya and Afrika Korps panzers (tanks) were rolling into Egypt. Rommel’s new positions stretched far into Allied territory, but his attempts to take Tobruk – which disrupted his supply lines – were beaten back and the Royal Navy continued to support the Allied defense. Rommel’s tiny but mobile force of short-pants-wearing Germans (and considerably less effective Italians) was unable to advance farther, and soon he was forced to consolidate his gains in North Africa. Allied attempts to retake Libya – Operations Brevity and Battleaxe – failed, but placed the Afrika Korps in a precarious position.

Wavell was replaced by General Claude Auchinleck, a Brit who was given massive new reinforcements from the Commonwealth armies. The new and enlarged British 8th Army assaulted the Afrika Korps at Tobruk as a part of Operation Crusader and finally pushed Rommel back to El Agheila in November 1941. General Auchinleck was again replaced by General Bernard Montgomery. The new officer – an eccentric man who, like Rommel, played by his own rules and, unlike Rommel, liked to wear oversized non-military sweaters – was soon thrown into chaos when the Afrika Korps counterattacked and pushed the 8th Army all the way back to El Alamein in Egypt. Rommel was only 140 km (90 miles) from Alexandria – but again, his advance was slowed by a lack of fuel and adequate allies. The German general was aware that he could not be adequately supplied so far from Libya, but he pressed on regardless.

Around this time, the Allies stopped using the Black Code (a code developed by the US State Department which had been “broken” by German intelligence) to transmit information. Thereafter, German command had no idea what the 8th Army was up to. Concurrently, codebreakers at Bletchley Park in England deciphered the German “Enigma” coding device. This new intelligence asset – codenamed Ultra – allowed the Allies to anticipate Axis movements for the rest of the war. From that point on, the Allies had the intelligence advantage.

The 2nd Battle of El Alamein

After months of resupply the British 8th Army was ready to attack again, supported by new M4 Sherman tanks as well as British Spitfires (advanced warplanes that had successfully held off German attacks during the Battle of Britain in 1940). Montgomery’s staff developed comprehensive predictions of casualties and abilities, and in October 1942 felt that the 8th Army was ready. On October 23rd, 195,000 Allies attacked the 116,000 Afrika Korps men at El Alamein with heavy air support from their Spitfires. As General “Monty” had predicted, the planes had a huge effect on Axis morale. German and Italian air assets were not adequately trained to support Afrika Korps ground troops, and as such were of little help during the battle. The Sherman tanks too were more than an equal match for the panzers, and managed to knock out many of them.

By early November, significant panzers had been removed from the Afrika Korps’ ranks (according to Monty’s calculations) and the breakout from El Alamein began. As the main Italian force withdrew to the West, Rommel ordered his remaining men to hang tight. By November 4th, the 8th Army had punched a 19 km (12 mile) hole in Rommel’s ring around El Alamein and the Axis were running low on ammunition and water. Parched and terrified by Allied airpower, the remaining Germans and elite Italian “Folgore” paratroopers fought until their last bullets were spent. Rommel telegraphed Hitler asking permission to retreat; the Fuhrer waited too long in replying, and at 5:30 pm that day Rommel pulled all his forces back to Mersa Matruh. By November 7th, the Afrika Korps was in full retreat and the Allies had forced a turning point in the North African Campaign.

On November 8th – just as the Axis withdrew from El Alamein for the last time – Americans and British troops landed in Algeria as a part of Operation Torch. They totally surprised French Vichy troops there (who were technically Axis soldiers), who surrendered immediately. From there, they pressed on and began engaging Afrika Korps units.

Before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein, we never had a defeat.”

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

The Tunisian Campaign

Immediately after the Torch landings, German and Italian forces rushed into Tunisia to reinforce the Afrika Korps. The new troops were just that – inexperienced and outclassed by the veteran troops of Rommel’s army. The new Eastern Task Force was unprepared for German offensives, and the US II Corps was humiliated at the Kasserine Pass by Rommel’s panzers. Luckily for the new Allied arrivals, the 8th Army had advanced far along the Mediterranean coast and was soon squeezing Axis-held Tunisia. The Allies had Rommel in a headlock, and in March of 1943, the German general returned to Europe for health reasons.

In the spring, the Allies attacked from both sides and on May 13th, 1943, the Afrika Korps under Italian General Giovanni Messe (who had inherited an unwinnable mess) surrendered completely. Over 275,000 Axis troops were captured, although a large number managed to escape to Europe. The North African Campaign was over, and the entire continent – including Italian Somalia and Ethiopia – was in Allied hands.

The Aftermath

The North African Campaign was a real test for all involved. For the British, it was their very first taste of “revenge” (for the bombing of England) and a crucial dose of real-world experience for them going forward. The Americans – who landed with Operation Torch – were forced to confront many of their tactical shortcomings and overhaul their Army in preparation for the invasion of Europe.

It was also a wake-up call for the Axis. Benito Mussolini’s boastings had been proven untrue; the fascist supermen were largely incapable of taking on the Allies and subsequently relied on German support. This frustrating revelation for German command meant that, going forward, many men and resources had to be devoted to defending the Mediterranean theatre (the “soft underbelly of Europe”, according to Churchill). This hampered their ability to conduct operations elsewhere, and ultimately hastened the demise of the German 3rd Reich. By the time of the fall of Tunisia, the Allies had had their very first taste of victory – and, as Churchill liked to say, the Allies continued to win from that point onwards.

ASAP Notes

In a hurry? Here are the ASAP notes on this topic.

- Who? The Allied 8th Army led by General Wavell and later, Montgomery. The force was comprised of British, Australian, Indian, Sudanese, New Zealand, South African, Rhodesian, Canadian, Tunisian, Moroccan, Algerian, and Greek troops, as well as “Free” Polish, Czech and French troops. They were later joined by Americans; Allied losses totaled about 48,000 killed. They faced off against the German and Italian Afrika Korps led by General Erwin Rommel AKA the Desert Fox. The Axis lost close to 42,000 men.

- Where? In North Africa. Battles took place in Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco and Libya, and in the waters of the Mediterranean.

- When? From June 10th, 1940, to May 13th, 1943 – over a thousand days.

- What? The North African Campaign was a series of major battles and minor skirmishes between the Allied and Axis in the region. Initially, Italians attacked British troops in Egypt but were chased back to El Agheila in Libya. Reinforced by the German Afrika Korps, they pushed back east and trapped the Commonwealth forces at Tobruk and El Alamein. After a series of battles, the reinforced British 8th Army pushed the overextended Afrika Korps back to Tunisia. A British-American landing in Algeria enabled the Allies to squeeze the Axis forces in Tunisia, and, despite a rough start for the new American troops, German and Italian forces surrendered the continent to the Allies in may of 1943.

- Why? Most European powers had colonial interests in Africa and the Middle East. Tensions rose as Italian imperial ambitions grew in the 1930s, and by 1940, their simply wasn’t enough elbow room left for either side. The continent provided an important foothold for the Allies for their inevitable invasion of Italy.

- Result: Allied victory. Despite German general Rommel’s ability to make do with limited forces and resources, superior Allied numbers eventually won out. The victory in North Africa – which came less than a year after the Soviet success at Stalingrad – was an important turning point for the Allies, who had essentially been kicked around by the Axis till that point.

Food for Thought

Like what you’ve read? Here are a couple essay questions/prompts to get you thinking. Good writing is all about answering questions the reader didn’t know they had, after all. These questions are to inspire further research, help with an academic paper, or maybe just get you thinking more about the topic.

- How did colonial troops view the conflict? Was their participation, broadly speaking, voluntary? Why or why not?

- What impact did the campaign have on local North Africans?

- Assess some of the Allies’ biggest tactical blunders, and how Rommel exploited them.

- Was the Italian Army ever truly ready to take on large scale military operations? Why or why not?

- Assess the importance of developments like the employment of the SAS or new intelligence breakthroughs like Ultra. What was their significance going forward?

Further Reading & Citations

Here are a couple useful sources for further reading or using to flesh out an essay. Remember to cite everything properly!

- Macintyre, Ben. Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War. Toronto: Penguin Random House, 2016.

- Fennell, Jonathan. Combat and Morale in the North African Campaign: The Eighth Army and the Path to El Alamein. Cambridge Military Histories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Moorehead, Alan. 2000. African trilogy: the North African campaign, 1940-43 : comprising Mediterranean front, A year of battle, the end in Africa. London: Cassell.

- Katz, David Brock. 2018. South Africans versus Rommel: the untold story of the desert war in World War II.

- Piekałkiewicz, Janusz. 1992. Rommel and the secret war in North Africa, 1941-1943: secret intelligence in the North African campaign. West Chester, Pa: Schiffer Pub.

Rommel’s biggest enemy was logistics – unfortunately he was too far stretched out for the German’s supply line to catch up with him.

LikeLike

Absolutely correct. Arguably far too ambitious and talented for his own good, given the resources available to him. Thanks for the input!

LikeLike